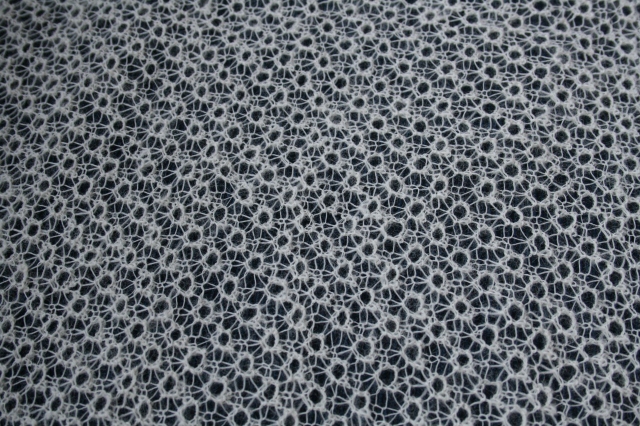

Remember the new-old project I wrote about in January last year? My aim was to knit a pattern I found in the archives at Southampton which dated back to 1867.

I’ll admit it – the project did get put on hold a little. I ordered and received the yarn in January 2014, and did a couple of swatches to determine my needle size and to familiarise myself with the pattern. That didn’t go as well as I had expected – it was really easy to make mistakes with the cobweb yarn and I found I needed long stretches of time and complete silence to make progress. So when I went to Australia for my three-month Institutional Visit I accidentally-on-purpose left the poor shawl in the UK…

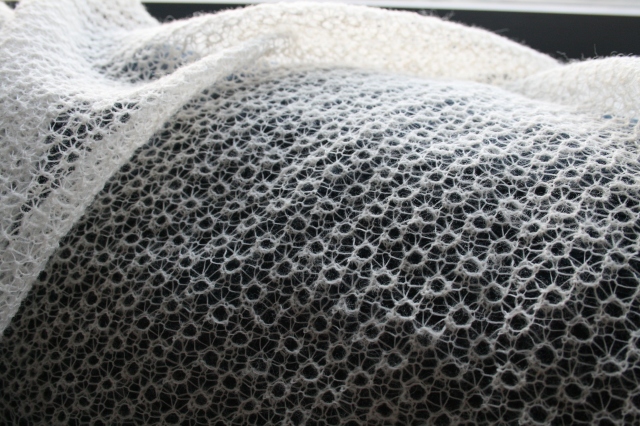

The guilt got a bit much so when I got back I promised I would work on it. I started with a vengeance in June 2014. I worked fairly steadily on it for about two months before getting distracted by a pretty cardigan, some sock yarn that just had to be knitted and then Christmas gifts. When January rolled around I resolved not to cast on any new projects until everything already on the needles was finished. I didn’t quite stick to that promise, but by March it was off the needles! Hurrah! Considering I worked on it on-and-off (although mostly off) for ten months it’s pretty small. It did grow when I blocked it, but it still didn’t look like much.

Looks are deceptive. This shawl is actually a lot. It is 53 repeats of a four-row pattern. Each row started off taking 15 minutes and ended up taking 1 hour (the length of the row gradually increased). That’s 96 hours on the body of the shawl, 9 hours on the border, and 2 hours sewing it together. I spent 8 hours swatching,12 hours making a sample version in aran weight yarn, 1 hour researching and buying the yarn. That’s 128 hours embodied in one shawl before even taking into account the research I did about the shawl, its designer, and the history of knitting.

The shawl isn’t just my time, either. It represents multiple histories colliding into one another. There’s Mlle. Riego‘s time designing the shawl in 1867, and relatedly, the leisure-time of the upper-class ladies who knitted from this very pattern. Then there’s the time of the Shetland women who made lace-knitting what it is, whilst they worked the land in the 1840s and simultaneously knitted in order to make an income. It’s the time of fashions, first seen in the Victorian era but now experiencing a resurgence as knitting re-gains popularity. It’s the time of the wool – grown and sorted in Shetland, spun in Yorkshire, posted to Bristol. It’s the time taken to learn a skill and do it properly, rather than reaching for a quick fix or buying a mass-produced item.

For something that’s only 4 months old, there’s a lot of history wrapped up in this little lace shawl. The process of making it taught me not only new knitting skills, but the histories and legacies of these skills too. I’m currently writing a couple of papers about what I learnt for publication, but between now and then I’ll do some short blog posts about some of the things I learned. Some of them are very practical and came from the process of knitting the shawl (such as the difference blocking lace work makes :-O), whilst others are more theoretical (such as how making can be considered as a qualitative method for social science research). For now, here are a few more photos of my finished shawl (Ravelled here).